A leading pioneer in the theatre lighting industry, Swiss-born Max Keller has been offering creative and technical solutions for the stage for more than 40 years.

Keller’s comprehensive knowledge and experience on some of the world’s most famous stages make him the definitive source for experts and those new to the field of stage lighting. His book, Faszination Licht, has been translated into multiple languages and is recognized as an indispensable handbook among the stage lighting community. In acknowledgment of his outstanding achievements, Keller was recently awarded the Federal Cross of Merit – a reward for loyal German citizens, equivalent to Britain’s Knighthood and France’s Legion of Honour.

Congratulations, Mr. Keller! For the first time in history, a lighting designer has been awarded a Federal Cross of Merit.

Thank you! Yes, that’s right. I didn’t expect it, after all, it’s very difficult to get such an award. It’s wonderful – a great personal success, maybe a highlight of my life’s work.

What does such an award mean for the profession of lighting design?

It’s very good because lighting design didn’t really exist in Germany as a profession until relatively recently. When I came to Berlin in 1968, you’d only have a lighting technician who turned on a light and added a colour filter, when a director requested it. In smaller theatres, it was the caretaker who was responsible for the lighting! At that time, there was no basic training. After two years, I thought to myself, ‘Man, there must be more to it.’ I went on a trip to the USA and saw a lot of productions while I was there. In the playbill, it always said: ‘Lighting design by…’ and I thought, ‘What are they doing? I’ve been doing this forever.’ Back home, in the theatre, if lighting was mentioned at all, it was only at the bottom of the list. Lighting was not seen as art.

Has that changed over time?

Completely! The profession really established itself 20 years ago. We make a contribution to a visual spectacle. If it’s done well, it’s a success for the entire production, because without light nothing happens. If I flick a switch, it’s dark [laughs].

What has been your experience in terms of developments in lighting design?

I was very ambitious and I was fortunate to find co-workers who wanted to help me. At the state theatre in Berlin, I was lucky to be working with directors and stage designers who promoted me and invested the necessary money, because lighting equipment is pretty expensive.

I bought my first HMI fixture from a company in Munich. It was a single film luminaire that didn’t always work as I wanted it to. Later, with ARRI, I developed some daylight fixtures – they’d been used in film before, but never in the theatre.

Over the years, there were some challenges to overcome, but I was triumphant. The Federal Cross award is the crowning glory. I retired five years ago, but I can hang the cross somewhere or, one day, it’ll feature in my obituary.

In 1968, when you started out, lighting was not considered as important as it is now. Why did you want to work in the field? What was it that appealed to you?

It was a long time ago. I’m Swiss-born and grew up in Basel. My parents took me to see The Magic Flute at Theater Basel, and the production was made only with projections. This was the first time I’d seen an opera and I was completely fascinated. I wondered how they did it. So, I bought a ticket for another production and afterward I wrote to the theatre saying: ‘Tell me, how do you do that?’ They replied, ‘Come to the theatre, we’ll show you.’ I was 17 years old, and I said, ‘I’m not going to go out anymore!’ I finished my apprenticeship and then started working in lighting at Theater Basel.

Did you think about it as a career, or was it pure passion for you?

It was passion. I really didn’t know at the time what could be achieved. In Recklinghausen, in Germany, a school for lighting technicians had just recently opened. I studied and took my exams there, and then applied to Berlin. When I joined the team there, it was a bit of a challenge. It took a little while for my colleagues to adjust – they weren’t used to having someone in that kind of role. I realised how important it is to have practical and talented partners by your side. If you have a bad director or a director who isn’t really interested in lighting, you can’t do anything. I was lucky, with me, it was all people who wanted it. They supported me in all things; I could hire staff and buy fixtures. You wouldn’t believe the kind of fixtures I worked with back then – lights from 1940. It was still a broken Berlin but it was a perfect career for me. It couldn’t have been better.

That sounds like a pioneering achievement!

At that time, most people didn’t understand anything about lighting. At first, I didn’t either. I wanted to change this, so I began to write brochures, which then became the first book. And, for ten years, there was only this one book in the German language. When it had sold out, I started work on a new version because I’d learned so much in the meantime. I’ve accumulated so much knowledge, not just about the perception of light, but also the technical information to back it up – and that’s even more exciting!

Have you been tempted to work with more recent developments in lighting, like LEDs?

I have no problems with LEDs. What is important is where and how you use the light. I witnessed the beginnings of LEDs in the theatre. At that time, the light was always too cold for me, but a lot has changed since then and LEDs have improved significantly. They’re great for specific purposes. In my opinion, a pure design with LEDs alone is questionable – perhaps if the decoration or the stage set is equally good…. Daylight technology is still the most important light for me. LEDs can’t achieve this. In Berlin in the early ‘70s, I worked with sodium lamps, which were used for street lighting. I dragged the street lights into the theatre and built spotlights. Light is light – you just have to use it correctly.

Do you think there could come a point when LEDs replace tungsten? Do you think technology could come that far?

I don’t know. At the moment I can’t imagine that, but maybe in 20 years. Tungsten fixtures are the backbone of the theatre. Then comes – as they say in Bavaria – the treats: the daylight, the special fixtures, the projections, the videos. But the basic light is almost always incandescent light, and that’s what you have to build upon.

You mentioned that you were lucky you always had directors who supported you in your vision. Have directors had a significant influence on you? Did you allow that? Or was a free hand indispensable for you?

In the early days, I always tried to find a compromise. There are always differences of opinion, and everyone in each department seeks the best for themselves. Some directors would ask for something a particular way and, if I didn’t think it was the right choice, I’d push back, but I wasn’t always successful. Later, when I’d written the books and had become famous in my field, I became tired of these sorts of discussions. I didn’t feel the need to negotiate anymore.

Did you reach a point where you thought ‘that’s enough for me’?

Yes, I thought, “I don’t want this anymore.” Sometimes, when I look at pictures, I do feel a desire to do it again, but basically, it boils down to the same thing – there’s nothing new; I’ve already done everything.

At the beginning of your career, how important was lighting to a production? How does that differ today?

At the beginning of your career, how important was lighting to a production? How does that differ today?

In the past, a production simply had to be lit. Then, it was whatever the director and the set designer asked for. It wasn’t so artistic. Of course, there were highlights sometimes, but it wasn’t designed, only operated. If it worked well, then it was fine. Today, that’s not the case. A lighting technician is just as much a part of a production as a costume designer. That’s a big step.

You’ve worked with ETC products. Tell us a little about your experience.

I’d been a Strand fan for years. Then, I decided to try ETC, but with a proviso: ‘If I’m going to buy ETC – or, as it was at the time, Transtechnik – I need certain things.’ And ETC did that for me. As a result, since then, I’ve always purchased lighting systems from ETC. Of course, I enjoyed jumping in the car, driving to Holzkirchen [Germany] and communicating on a technical level. It was a satisfying collaboration, with Willi Sterff, who founded the company. It was great!

Did you ever call upon ETC for technical support?

The service has always worked for me. I never had any problems. I’ve never been disappointed by ETC, or other companies because they understood my needs.

Was it important for you to be involved and know the systems to get the maximum benefit?

Yes, the plastic color filters are the best example. Once, I was missing a color and I had a particular idea about how the color should look. The company Rosco then made my specific color – and they still exist today.

What would you say to the next generation wanting to work in this industry? What do they need to bring?

In this day and age, you have to be well educated. You must be able to do more than distinguish between blue, green and yellow; you need to be familiar with the technical structure. Also, some directors really value philosophical input, and if you can demonstrate that kind of knowledge, you can go much further. You need to find people who want to work closely with you, that can be quite difficult, and you need to know your stuff.

That sounds quite demanding.

It is. Lighting is a huge area. It’s not just about turning a switch on and off. In addition, you need good people. If you’re a resident lighting designer in a theatre, you can drive the department and the development of staff. However, if you’re a guest somewhere, you expect to find professionals working there who can understand and implement what you say.

This is an English adaptation of an interview originally conducted in German.

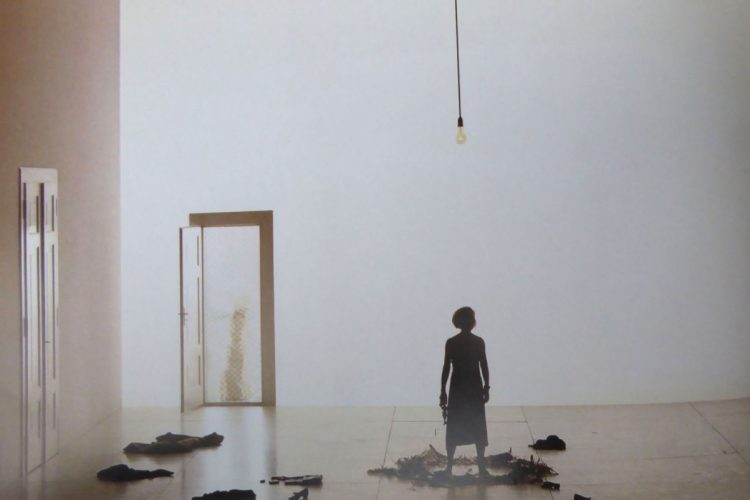

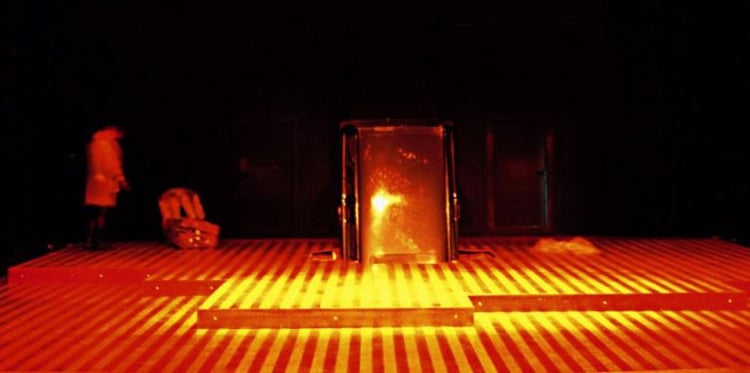

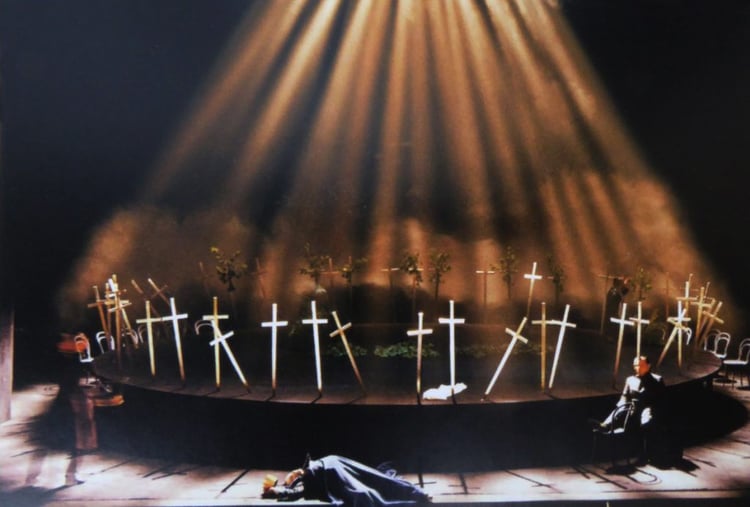

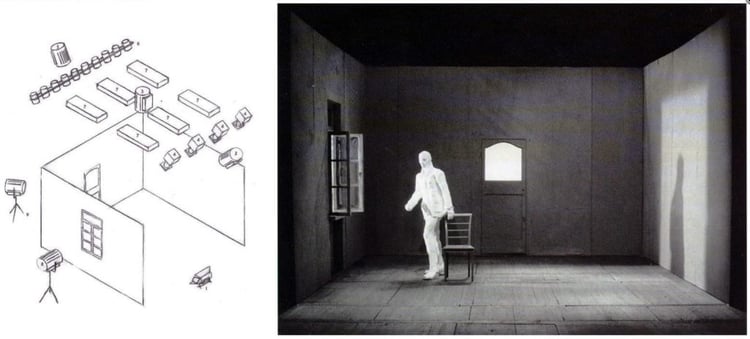

Non-captioned images courtesy of Max Keller, taken from his book Faszination Licht.