Welcome to the Monthly(ish) Museum, where we make periodic dives into ETC’s collection of lighting industry gear and ephemera. In this installment: piano boards.

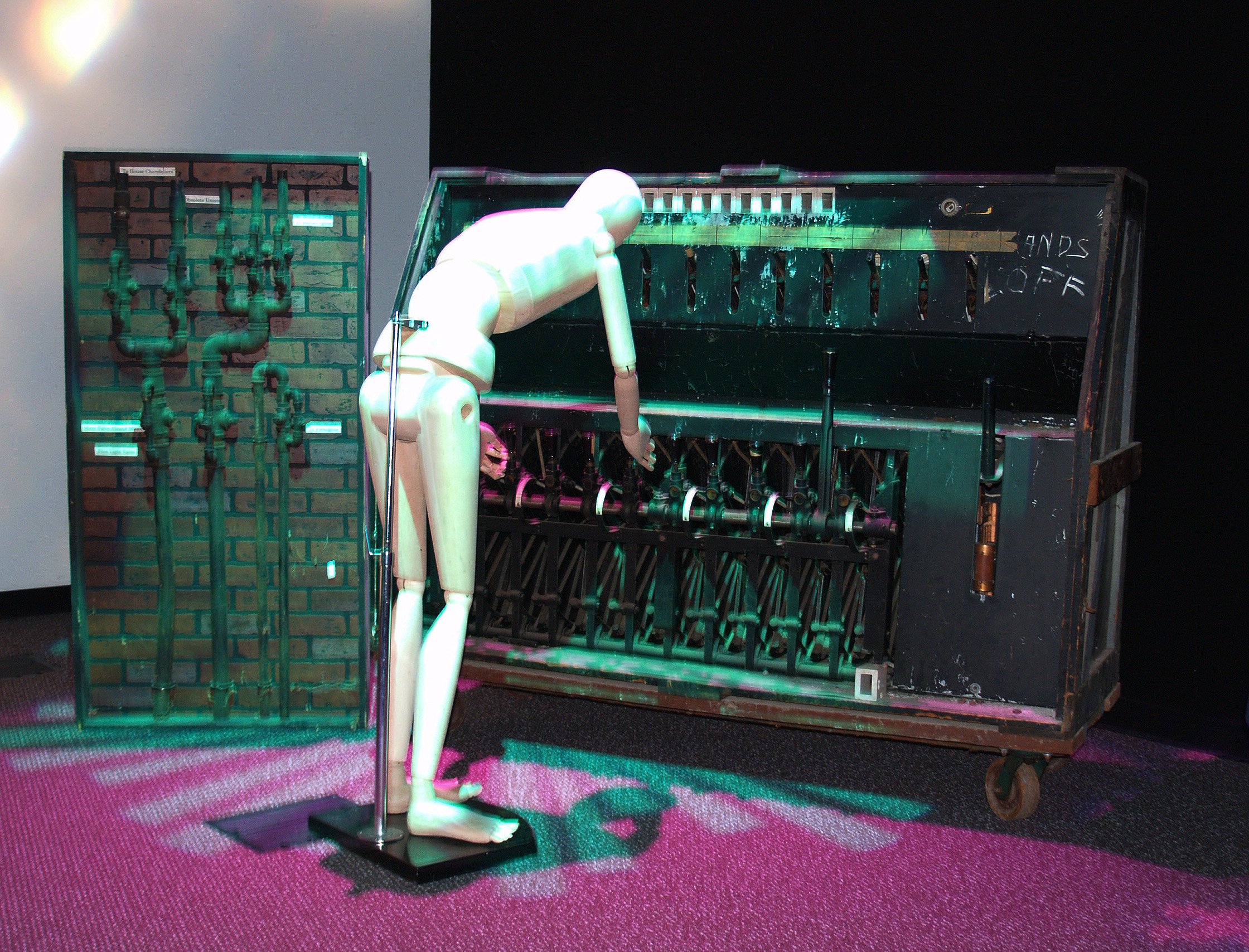

By the time ETC partnered with LMI in the early ’90s and started making dimmers, dimming control was largely electronic. Still, over the years, ETC has come into possession of several full and partial manual dimming systems, which now live in our “museum” of lighting history. In addition to the physical cool factor – a mechanical aesthetic right out of a dieselpunk Metropolis fantasia – these units are part of a legacy of lighting control that still echoes through console theory and programming today.

For those in the younger crowd who’ve never personally interacted with these leviathans (myself included; I almost got my hands on one once in a downtown NYC venue, but it was removed just before our show loaded in), here’s a little background information:

Hands-on lighting

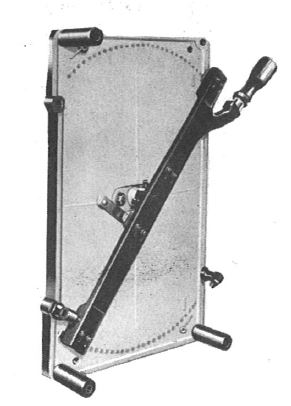

The “piano board” moniker comes from the unit’s resemblance to an upright piano. Also called “portable boards” or “road boards,” they were widely used from the early 20th century through the 1970s. Each unit ran on DC power and consisted of a row of interlocking or non-interlocking resistance dimmers (controlled by the operator using the large handles pictured above), a switch and a fuse for each circuit, and a master switch that would turn everything off.

Dimmers would not function properly without a full load. Individual control of lower-wattage lights was often achieved by connecting the dimmer’s circuit to a small preset board, which would provide a constant load and allow the operator to select individual light(s) to be controlled. Other times, ghost loads were added to supplement the lights on a dimmer.

Even when dimmed all the way out, each dimmer generated a large amount of heat. Operators used the switches to power off any dimmers that were not actively in use, but it was still a very hot working environment.

The boards were positioned across from each other in two rows, allowing a single operator to run two sets of levers at once. A typical large show would have eight boards and four operators – the maximum number of operators (and therefore dimmers) for which most productions were willing to pay. Needless to say, the lighting rigs were generally much smaller than they are today.

Executing a cue required great skill and coordination. Piano board operators would directly manipulate the levers to predetermined levels for each cue, counting out the fade times. To fade multiple dimmers at once, the operator would engage each dimmer to the master by turning the handle, start the fade using the master lever, and then unlock each individual dimmer handle as it reached its target level.

“There wasn’t a lot of precision in setting levels,” recalls Steve Terry, ETC’s Vice President of R&D, “You could sort of do off, full, 2, and 7.”

There was an art to assigning cues among the operators. Fast fades – which required a sudden burst of muscle to move a lot of levers at once – might be assigned to the strongest operators. The most demonstrably patient crew member might be assigned the long, subtle fades.

Because a dimmer stayed at its level until the operator physically moved the handle to a new position, piano boards gave rise to the “tracking” approach to control theory, in which only level changes are recorded into a cue. Many of today’s desks – including the Eos family consoles – still utilize this control philosophy.

Our specimen

Like many other items stored at ETC, the board came to us from Doug Taylor, who amassed a collection at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, originally in the hopes of donating it to the USITT archives. Taylor obtained the board from Associated Theatrical Contractors in Kansas City, MO. The accompanying notes indicate that it was last used as a stage prop for a production of The Dresser. It is unclear whether the “Hands Off” message scrawled on the face plate was the work of the props master or a general admonishment from the board’s days in active service.

This unit likely dates from the 1940’s, ’50s or ’60s, though the precise age and manufacturer is unknown. Most piano boards were built by rental shops, which would purchase the dimmers and the linkages and then build the metal and wood enclosures themselves. The black paint on the metal served a very practical purpose: because the electrical elements were not grounded, the entire metal box would be electrified to some extent by the inductive current. The layers of black paint – typically re-applied between every rental – helped to protect the operators from accidental shocks.

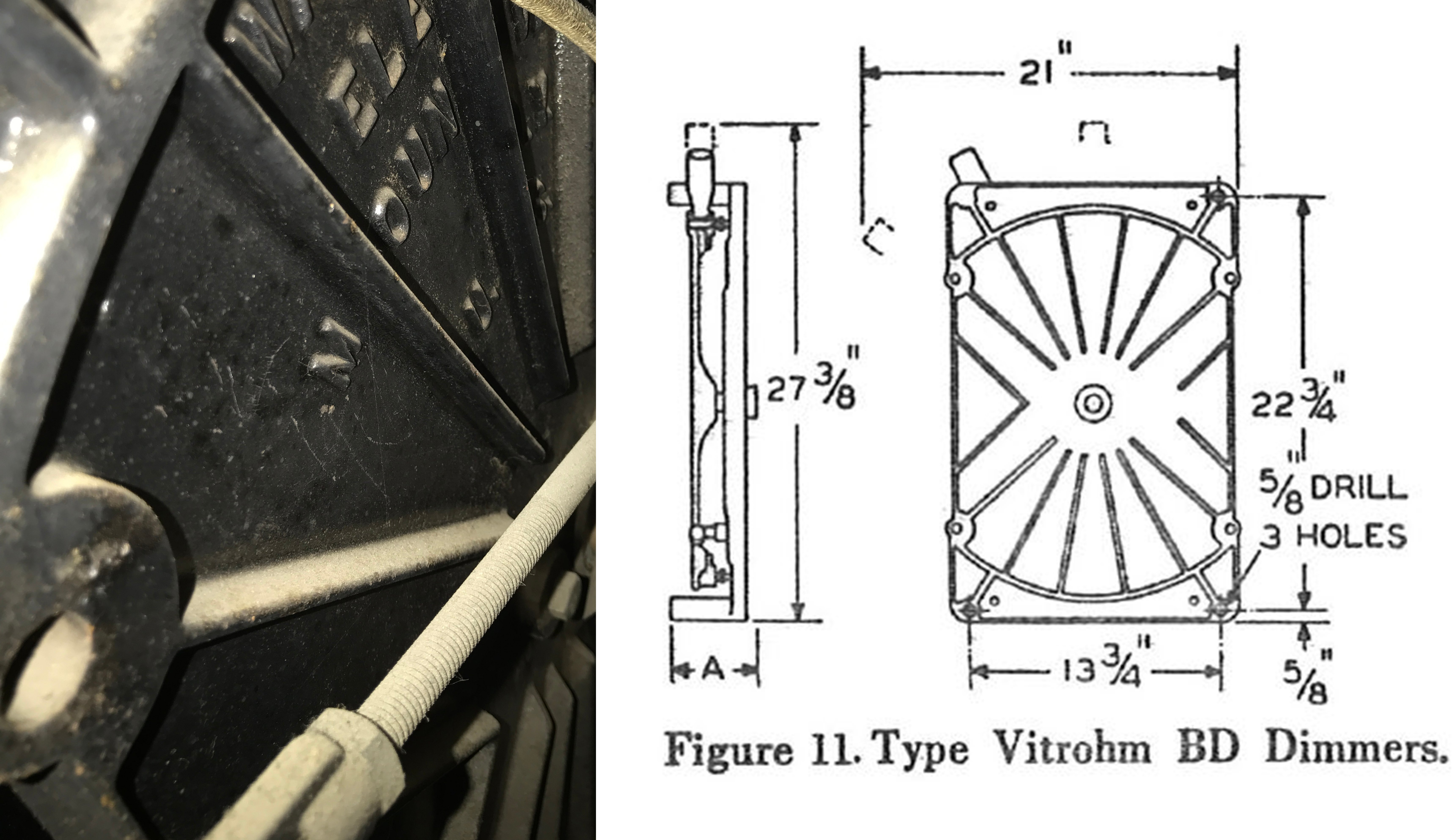

The dimmers in the above unit bear the manufacturer’s mark of Ward Leonard Electric Co. of Mount Vernon, NY, and are a close visual match for the “Vitrohm BD Dimmers” listed in a 1965 sales bulletin in our archives:

From Ward Leonard bulletin 71: “Vitrohm non-interlocking dimmers,” October, 1965:

Type BD Dimmers may be banked together and individually operated to control two or more circuits. The operating levers may be arranged for interlocking to a master lever similar to that used on Interlocking Type dimmers

The image at left shows the reverse side of the Vitrohm dimmer plate, containing the electrical contacts. Moving the handle caused the attached brushes to rotate around the contacts on the plate, providing varying degrees of resistance.

The image at left shows the reverse side of the Vitrohm dimmer plate, containing the electrical contacts. Moving the handle caused the attached brushes to rotate around the contacts on the plate, providing varying degrees of resistance.

Likely due to their compact, rectangular shape, the Vitrohm dimmers listed in the bulletin have only 58 dimming steps. The interlocking dimmers more typically used in theatrical piano boards were fully round, accommodating more contacts (110 steps) for smoother dimming.

Additional sources:

Pilbrow, Richard. Stage Lighting. New York, NY, Von Nostrand Reinhold, 1970.

Heffner, Hubert C., Samuel Selden, Hunton D. Sellman, Fairfax P. Walkup, Tom Rezzuto, and Kenneth K. Jones. Modern Theatre Practice. 5th ed. New York, NY: Meredith Corporation, 1973.

Do you have memories to share about using piano boards? Do you know something about the units pictured above? Our archives are a work in progress, and we’d love your feedback. Let us know in the comments or email us at blog@etcconnect.com.