Out of Control is a recurring series written by Nick Gonsman of ETC NYC. Each installment sheds light on an aspect of the theory and practice of entertainment lighting control. Today’s topic: Eos palette and preset modifiers.

Intro.

As I have traveled around from venue to venue over the past few months, there has been a question that seems to crop up in nearly every Eos programming discussion – what do the palette and preset modifiers do, and why would you use them? In short, making a palette or a preset Absolute or Locked determines how that data is recalled, and how changes are stored back to the target. But before we delve into what the modifiers do, we need to first understand the standard behavior of palettes and presets.

Palettes & Presets are Referenced data.

Eos Family consoles – and most modern lighting control systems – can store data for playback in two ways: as Absolute or Referenced. To understand the difference, let’s look at a moving light’s pan and tilt values.

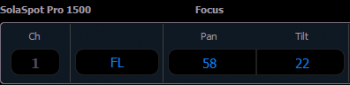

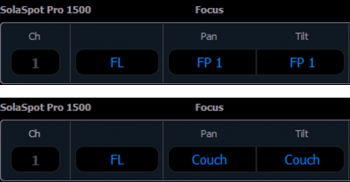

I need to light the couch. I drive my mover to it, which yields pan: 58, tilt: 22. I can then store those values directly into a cue. This data is Absolute – hard values are stored in the cue, and when it is played back the board fades the parameters to the cue’s stored values. Pretty straightforward – it’s the way we’ve been storing and playing back intensity data since the proverbial dawn of computerized lighting control.

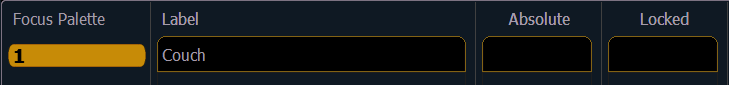

But I can do more. With my moving light at the same values, I can record the data into Focus Palette 1. I can label it “Couch.” And, once the light is set in that focus palette, I can record that information into the cue. In this case, the cue doesn’t record pan: 58, tilt: 22. Instead, it records pan: FP1, tilt: FP1 – or displayed another way – pan: “Couch,” tilt: “Couch.” So when the cue is fired, it references Focus Palette 1, and plays back the data stored in it. For this reason, we call palettes and presets Referenced data.

Storing data in this way has three main advantages. First, I can label a palette – so I have given context to what would otherwise just be a collection of numbers. Second, I can now reuse this information elsewhere in my show – so every time we go back to “Couch,” I can quickly get all my parameters there. And third, every cue I store “Couch” in uses the same bucket of data – so when the director moves the couch 20 minutes before first preview (which never happens), I update the data in “Couch,” and all cues that reference it are instantly changed, too.

Simply put, Referenced data is pretty sweet, and is an essential part of programming a modern rig. But because palettes and presets are this special type of data, we need some tools to allow exceptions. Enter stage left: palette and preset modifiers.

Always Absolute.

When you put a palette or preset onto a channel – like [1] [Focus Palette] [1] [Enter] – and store a cue, you are storing the reference. But sometimes you want that palette to simply be a shortcut that dumps a collection of absolute data on stage quickly; you don’t want the information to continue to be tethered to the reference bucket. Sure, you could put the palette on the channel, and then hit the {make absolute} soft key, but that extra step is tiresome if you never want the data to be stored with a reference. To make a target always absolute, from live or the target list, type [Focus Palette] [1] {Absolute} [Enter]. Now when you type [1] [Focus Palette] [1] [Enter] in Live, you get pan: 58, tilt: 22.

Got it, Gonsman. But why do I care how data is recalled and stored?

To continue our example – the “Couch” Focus Palette is associated to an object whose location could change, based on the whims of a director. I want to store the reference, because when the couch does move, I have one place to make the change. But if I am using a Focus Palette as a shortcut to get my fixture to a general area of the stage quicker than I can wheel it in – like Downstage Left – I don’t want to store the reference to that data, and I don’t need to worry about modifying that data easily across my show file (if Down Left is moving in your venue, updating your cues is probably the least of your worries).

Another example is using intensity palettes for balanced looks. Designers often like to construct looks with many conventionals at different levels, and want to access them quickly to build full stage treatments. So using intensity palettes works great. But designers don’t tend to like looking up at their RVI, and seeing 60 channels say “IP32” as their levels. Making sure my intensity palettes are set to Always Absolute lets me recall the data quickly, and lets the designer see what she’s expecting.

Locked.

Sometimes you want to store a reference in a cue, even if you aren’t going to want to modify it globally later. For example, looking at your LED fixture and seeing it is at “R26” is more valuable information than a string of emitter levels. But it is highly unlikely that you will want to globally redefine “R26” halfway through your process.

Here’s a common scenario. My CP26 (which has my best approximation of R26 in it) is stored in a cue. After seeing actors and costumes on stage, the designer wants to tweak the color. We go to the cue, she nudges some of the levels, and we see red “R”s next to my parameters. These are reminding me that underneath my manual changes, there is still referenced data stored. She likes the changes, and she wants to update them to this cue.

In an Update All scenario, the console wants to save the changes to the source of the data. And as those little R’s are reminding me, the data didn’t come from Absolute values stored in the cue itself, but from Color Palette 26. So when I Update All, I will write over my R26 values with the new modifications. This works great for our couch example – where I wanted to redefine the couch position for the whole show. But I doubt the designer’s intent is to redefine R26 globally.

Again, I could manage this on a change-by-change basis, but that’s a lot of wasted time. After all, happy hour doesn’t last all night. Wouldn’t it be nice if I could set my “only a shortcut, but useful as a label” palettes to deflect incoming changes? Well, it’s your lucky tech day.

First, I’ll lock Color Palette 26 – from live or the target list, type [Color Palette] [26] {Lock} [Enter]. I then hit [Update] {All} [Enter], and the following dialogue occurs in the console:

CP26: I’m locked. I rather think you won’t.

UPDATE HANDLER: Fine. Be that way. I’m just going to ignore you, and save these changes as Absolute data into the cue.

CP26: Fine. I’ll keep my original data for the rest of the cues that are using me. But I’ll still see you at Preset 4’s birthday party?

Update sidebar.

Incidentally, the desk’s default setting for Update is Make Absolute, which you may have guessed takes any changes being saved, ditches the reference, and saves them as Absolute data in the cue. While this mode is viewed by many as the “safest” (it won’t allow you to accidentally modify a palette or preset that you may be using elsewhere), it is also destroys all modified references and is a blunt instrument when it comes to data management. If you’re going to become a power user of palettes and presets with tools like Locked, Update All gives you the ultimate control.

Outro.

The palette and preset modifiers of Always Absolute and Locked can elevate your programming – allowing you to sub-categorize targets, not just based on what parameters are stored in them, but how you want to deploy them. I’ve tried to cover as many of the bases as I could in a post, but like many features, there are lots of nuances to these tools. But practice makes perfect – in a non-tech situation, flip them on and see what happens. Once you are comfortable with their behaviors, I have no doubt you’ll be finding use-cases you didn’t even know you needed.

Like what you saw? Did I mess something up? Got something you want to know more about, or have a tip to share? My inbox is always open: nick.gonsman@etcconnect.com.